Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is undoubtedly today’s biggest national and global security threat, situated precariously at the intersection of public health, military, and economic concerns. With many states still struggling to respond to domestic infection levels, governments are responding to the pandemic with increasing patterns of isolationism – lockdowns, stricter travel policies, and border closures are the new norm. The pandemic is transforming the current understanding of global migration and mobility, with refugees and other displaced persons being left behind and forgotten in the process.

The UNHCR estimates that 167 countries have implemented some degree of border closure for virus containment, with 57 of those countries making no exception for asylum seekers. This adds a new layer of complexity to refugee entry systems which were over-run, under-digitalized, and generally ineffective even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Europe, the European Union asylum processing remains technologically stunted and all hearings have been halted for an indefinite period time. Greek refugee camps that are infamous for overcrowding have been rendered virtually incapable of meeting basic human needs due to the spread of the virus, opting for strict containment to meet the demands of panic-stricken citizens.

Such pre-existing issues are being further exacerbated as available social safety nets are pulled away, and there are a number of ramifications that can be expected from increasing border closures and restrictive entry policies.

Policies that are meant to mitigate COVID-19 infection rates may be counter-intuitive and, instead, trigger mass refugee migration due to the lack of social safety nets, which are necessary to protect the economic and human rights for refugees and asylum seekers. Syrian refugees in Turkey are choosing to return to the Idlib, Syria, rather than remaining in refugee camps where concerns about virus infection are growing exponentially. Venezuelan refugees in Columbia, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, and Argentina have little option but to return home as joblessness and homelessness become prevalent.

Furthermore, human rights for refugees and asylum seekers are less likely to be prioritized in immigration systems and border security following the pandemic. Countries that have hardline stances on immigration and refugees are using COVID-19 as an opportunity to toughen policies that include refusing entry and deportation. In April, Malaysia denied 200 Rohingya refugees entry, adding to the number of refugees trapped at sea and dying in cramped boats after being turned away. Even host countries that have a reputation for open immigration policies, such as Canada, have closed their borders with no exceptions for displaced persons and will likely face difficulty loosening restrictions.

The impact of extended border control will be especially difficult to mitigate post-COVID-19 as governments are increasingly weaponizing fear and anti-refugee sentiment, which will negatively influence host community perception of displaced persons. For example, government leaders in Hungary and Italy have made open, accusatory statements regarding the presence of migrants and COVID-19, which will directly affect the ability of refugees and asylum seekers to request protection in respective host countries.

As global mobilization is minimized and new security issues emerge by the day, COVID-19 is exposing new and old challenges of humanitarian protection for refugees. It is it likely that signatory countries to the 1951 Refugee Conventionwill increasingly resist the practice of non-refoulment, or the practice of returning refugees to their country of origin, in the post-COVID era, signaling danger of perpetual displacement for refugees and asylum seekers. Developing flexible solutions for those situated in refugee camps will prove to be an even more difficult task. Current methods of deportation, containment at detention camps, and refugee camps do not address key issues or prevent further vulnerability to COVID-19. To prevent a future where refugees are no longer left behind, it is essential that governments work to retain and constitute social safety nets and intentionally accommodate refugees and displaced persons in their border policies.

Yihyun Andrea Kwon is a senior studying B.A. Global Affairs with concentrations in Human Security and Global Governance at George Mason University. She is also minoring in Conflict Analysis and Resolution. Her current research interests lie in the interconnection of international security policies and human security in the East Asian region, South Korean soft power and diplomacy, and refugee/displaced persons policymaking.

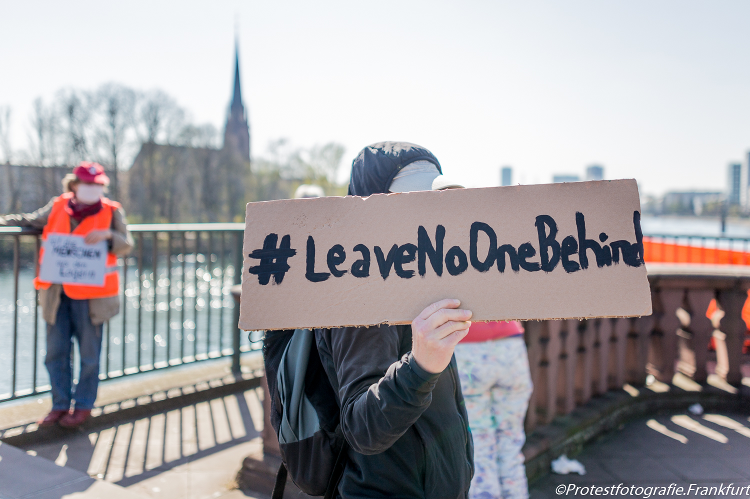

Photo can be found here.