As Shanghai nears a month of lockdown, residents of Beijing are rushing to stockpile food and supplies following reports of new cases in the city and the Monday night announcement that 11 of the city’s 16 districts will be subject to mandatory testing. As the Chinese Community Party (CCP) clings to its “Zero-COVID” policies, the realities of China’s lackluster inactivated vaccines combine with the threat of further supply chain issues as the Yangtze River Delta region shuts down to make it clear once again—China poses a major threat to global and US national health security that is unlikely to be effectively addressed through international organizations and laws.

A History of Cover-Ups

At least twice before the COVID-19 pandemic, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) concealed major outbreaks, including the HIV/AIDS blood scandal in Henan in the 1990s and SARS in the early 2000s. In the case of the latter, at least 8,098 contracted the novel disease globally, with 774 confirmed deaths. Chinese health officials were aware of the unusual outbreak as early as mid-November of 2002, but a media blackout on the topic was implemented and the PRC shared little information with the World Health Organization (WHO) until April of 2003, at which point it was already spreading internationally.

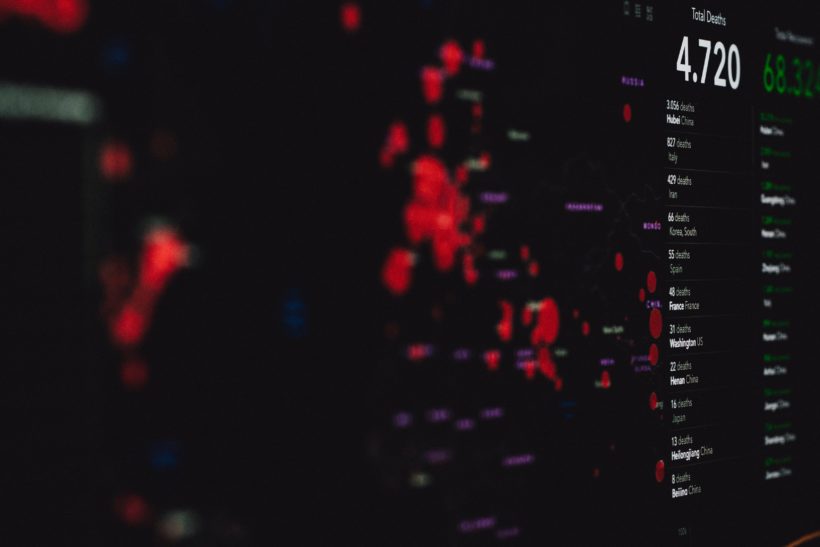

The world has now grappled with COVID-19 for nearly two and a half years now, enduring economic devastation and racking up a death count estimated as high as 15 million. Though this disease first attracted attention in Wuhan in late 2019, its precise origin has not been definitively determined, despite the global hardship it has caused. In fact, the 2022 Annual Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community reaffirmed that the IC still cannot reach a consensus on the origin of SARS-CoV-2 (the causative agent of COVID-19), something that becomes even more unlikely as time drags on. These failures to report outbreaks and share critical information with the international community cost lives by delaying response efforts and wasting precious time.

Combatting Future Chinese Health Threats

China’s repeated failures to notify the WHO promptly of the initial outbreaks of SARS and COVID-19 violate the International Health Regulations (IHR), a legally binding instrument of international law designed “to prevent, protect against, control and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risks, and which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade.” Despite this, it is unlikely the PRC will be more forthcoming in notifying the international community the next time something like this happens, likely opting instead to once again conceal the outbreak in a bid to quash it before it has the opportunity to harm the Party’s image. The IHR lack an enforcement mechanism and, given global dependence on China, it is unlikely the international community will turn to other means of enforcement, such as sanctions, at a level sufficient to compel better cooperation with the IHR in the near future.

Two of the three pandemics of this century so far have been caused by novel diseases that emerged in China. Southern China has also been identified as a hotbed for emerging infectious diseases, so there is a good chance something similar will happen in the coming decades. Because of the health security threat posed by an uncompromising and non-cooperative China, the US should take actions to improve its own health security preparedness. The US has a number of gaps in its preparedness, some of the most important of which are susceptibility to health mis- and disinformation, a patchwork public health funding system, and challenges in healthcare access and equity and chronic disease management. Addressing challenges like these will improve public health and health outcomes generally while also preparing for the realities of poor international enforcement of global health laws and a rival great power that does not abide by these rules.

Conclusion

The ramifications of dealing with a great power that views global health as another convenient avenue for competition will likely be severe. This can already be seen in China’s attempts to spread the lie that the US Army introduced SARS-CoV-2 to Wuhan during the 2019 Military World Games and the country’s efforts to leverage pandemic response to expand its influence in Southeast Asia. These efforts detract from the severity of this pandemic, making it instead international political fodder. The fundamental problem with this is that global health security is not a zero-sum political game, but a threat area where everyone can lose badly, an especially pressing fact as climate change and human population growth further drive infectious disease threats. As it is unlikely that the PRC will change its behavior, the US should take major actions in the coming inter-pandemic period to improve its preparedness in time for the next major global health crisis.

Danyale C. Kellogg is a Biodefense PhD student, Presidential Scholar, and graduate research assistant at the Schar School. She is currently Managing Editor of the Pandora Report, a Defense Policy Junior Fellow at the National Defense Industrial Association, Young Professional’s in Foreign Policy’s Global Health Fellow, a Pacific Forum Young Leader, and a member of the US-Japan Next Generation Leaders Initiative. In 2021, she earned her Master of International Affairs on the National Security track with concentrations in China Studies and Biosecurity from the Bush School at Texas A&M University after completing her capstone with US Indo-Pacific Command’s China Strategic Focus Group. She also earned a Global Health Graduate Certificate from the Texas A&M School of Public Health where her research focused on ROK preparedness for an infectious disease outbreak on the Korean Peninsula. In 2019, she earned a BA in History, Paideia with Distinction in Global Health, after completing her senior thesis on US strategic and intelligence failures during the Korean War. She is an alumna Women in Defense Scholar and has studied at Ewha Womans University and Korea University in Seoul as well as Universidad de Los Andes in Santiago. While at Schar, she has completed George Washington University’s Institute for Korean Studies’ North Korea Program as well as the Medical Management of Chemical and Biological Casualties Course, offered by the US Army Medical Research Institutes of Chemical Defense and Infectious Disease. She has interned with the Departments of Defense, Health and Human Services, and Homeland Security, among other organizations. Her research interests include East Asia, global health security, defense policy, grand strategy, and the intersection of public health and national security. Her work has appeared in National Defense, Global Security Review, and Geopolitical Monitor.

Photo can be found here.