Session 1

A Debate about Alliances and their Durability

Featuring

Rajan Menon, author of The End of Alliances (2007)

Kori Schake, American Enterprise Institute

Eduard Soler, author of “Liquid Alliances in the Middle East”

Moderator: Ellen Laipson

The first session focused on the big picture: are alliances still relevant and useful to address 21st century security challenges? The conversation was moderated by CSPS Director Ellen Laipson

The distinguished list of guest speakers included Dr. Rajan Menon, who currently holds the Anne and Bernard Spitzer Chair in international relations at the City University of New York; Kori Schake, who recently became the Director of Foreign and Defense Policy at the American Enterprise Institute and has served in key positions inside the State and Defense Departments; and Eduard Soler, a Senior Research Fellow at the Barcelona Center for International Affairs.

Dr. Menon, referencing his 2007 book End of Alliances, argued that the strategic circumstances which favored formal alliance relationships during the Cold War no longer exist. In the European context, this means that geopolitical developments have eroded NATO’s raison d’être out from under it. We can no longer summarize NATO’s mission with the succinct “deter and defeat the Soviets if necessary.” In light of this, Menon argued that a transition towards a more autonomous European security architecture is both feasible and desirable considering the economic might of the Eurozone and the relative weakness of modern Russia. Moreover, in light of the American refocus to the Asia-Pacific, what Menon labeled “the main event for the rest of the century,” such a reframing of the transatlantic relationship would avoid the dispersion of the US’ limited strategic resources. The relationship, to Menon, has become “codependent” and no longer optimal.

Kori Schake responded with a more optimistic view of the utility and adaptability provided by formal alliances despite changing strategic circumstances. In fact, she argued, the complexification of NATO’s core mission that Menon described shows that adaptations have already occurred. NATO provides a mechanism to solve problems by identifying commonalities among member-states. Friction has always been present, yet the alliance endures because “we feel safer holding each other’s hand.” The Russians labor to keep eastern European countries on its periphery “unstable, poorer, and adrift.” NATO’s responses to Russian provocations show the alliance’s skill in remaining firm, deterring conventional threats, and doing so without unnecessarily stirring Russian insecurity. Crucially, the alliance could not, in Schake’s view, operate without a strong American presence and engagement. The leading role of the US bridges the Atlantic and keeps the alliance unified.

Eduard Soler tackled the question of the nature of the Russian threat, an integral part of the NATO debate. For him, it is misleading to conflate a weakened Russian economy with a lower threat perception across the European continent. He remarked that if one told an Estonian official that the Russian threat had receded, he would not understand the contention. Different countries across Europe “feel it very differently.” He reminded the panel that Russia continues to actively work “to undermine not only NATO but also the European Union.” Moreover, these activities are not limited to the war in Ukraine, election meddling, and cyber attacks on Baltic states. Russia also benefits from instability in the southern and western Mediterranean. Political upheaval yields migration inflows, which tax the capacity of European governments, exacerbate interstate fissures, and strengthen rightwing political movements in European political systems that tend to align with Russian interests.

Turning towards Asia, Menon pointed to the “crossroads” at which Japan finds itself. Though its strategic situation is less fortunate than Europe – a more economically, demographically, and technologically threatening neighbor – the recent behavior of the Chinese in neighboring waters and airspace forces Japan to reevaluate its defense and security policies. He posed the important question: can Japan reasonably continue to rely on American military predominance in the East China Sea and North Pacific more broadly? If not, their 1% of GDP spent on defense might quickly become untenable. The Japan-India bilateral relationship is the key relationship to watch moving forward. These countries had “very little to do with one another” for a long period of time but have worked to deepen ties in recent years.

Schake then turned to Asia, where she highlighted some of the key developments in Japanese security policy as it relates to alliances, including the dispatch of MSDF forces to the Indian Ocean to provide logistical aid to coalition operations in Afghanistan and more recent training missions of the Japanese Coast Guard in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam. She agreed with Menon that the Japan-India relationship is a critical one but remained cautious toward the prospects of anything resembling a formal alliance. The Indian government and people still take pride in being nonaligned, “and in fact the leader of the nonaligned movement.” China’s aggression on the Indian border, however, combined with the “galloping pace of China’s rise,” adds incentives to India deepening security relationships with countries other than the US.

Soler brought the panel’s discussion to the Middle East, where he introduced his concept of “liquid alliances.” Drawing on work from sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, Soler developed the notion of liquid alliances as temporally, geographically, and topically delimited groupings which arise over specific issues in times of uncertainty and fear. The “triangle” of the UAE, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia exemplify how similar interests in one region over a specific issue do not map neatly onto other issues and areas, leading to flexible security arrangements void of concrete and universal mutual commitments. To cope with rapidly changing political and security environments, states in the Middle East turn to improving bilateral relationships. Broader attempts to formalize these liquid alliances “have mostly failed in the Middle East.” Soler pointed to the Arab League, which solidified for a brief period following the Arab Uprising but quickly dissolved as “a flash in the pan,” as case and point of the difficulties involved in formally institutionalizing security agreements in the Middle East.

Prepared by Connor Monie, PhD Candidate, Schar School

Session 2

Current Alliances and their Challenges

Featuring

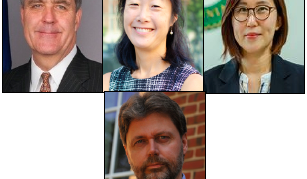

Former US Ambassador to NATO General Douglas Lute

Yuki Tatsumi, Director of Japan program at Stimson

Soyoung Kwon, professor at George Mason’s Korea campus

Moderator: Colin Dueck

The second session, moderated by Schar School Professor Colin Dueck, focused on current alliances and their challenges: NATO, Japan, and South Korea. General Douglas Lute, the former US Ambassador to NATO and former Deputy National Security Advisor for Iraq and Afghanistan, Yuki Tatsumi, Senior Fellow and Director of the Japan Program at the Stimson Center, and Dr. Soyoung Kwon, the Director of Security Policy Studies at George Mason-Korea formed the panel.

Dr. Dueck first asked each panelist about the state of the alliances in each of their regions of expertise. General Lute stated that while NATO needs to refresh its mission, he is optimistic about its ability to respond, citing the numerous transformations it has undergone in its 70 years of existence. There are new challenges, including a growing Chinese diplomatic influence in Europe, hybrid warfare and grey zone conflicts, and cyber threats, but General Lute argued that the biggest challenge is presently internal rather than external. The core values underlying NATO – democracy, individual liberty, and rule of law – are being threatened by the political developments in allied states, like Turkey, Hungary, and Poland.

Despite the Trump Administration’s pattern of downplaying the role of alliances, General Lute cited the importance of alliances like NATO, especially to long-standing conflicts. Looking at Afghanistan, the US has had forty partners active in the conflict for twenty years. General Lute did critique the US for its fixation on military tools at the cost of other methods of resolving conflicts, stressing the importance of aligning ends, ways and means with deep knowledge of the terrain and peoples in future conflicts. Despite the long-running conflicts that the US has been engaged in, General Lute finds it highly unlikely that there will be a movement to a European-led security system in the short-term. This is due to the overlap between NATO and EU membership and the fact that the US remains an indispensable ally in hard military terms.

When examining relations in East Asia, both Ms. Tatsumi and Dr. Kwon cited challenges posed by four years of the Trump administration. In Japan, Ms. Tatsumi asserted that Japanese officials continue to prioritize a close alliance with the US, but the Trump administration’s unpredictability has created a demand for greater autonomy in security decision-making. Like NATO, the alliance has weathered the end of the Cold War, and Ms. Tatsumi does not believe that there is an alternative to the US to anchor Japanese security policy. According to Dr. Kwon, the US alliance with South Korea had likewise gone through numerous changes and was the linchpin of security in the region and for Korea. Still, there have been increasing demands for autonomy in South Korea, and domestic politics in Korea reflect a divide across the society about reliance on the US versus more independence in security policy.

The Trump Administration’s transactional approach to alliances has perturbed numerous alliance partners. The $5 billion demand from the US for its continued presence in South Korea, a 400 percent increase from the previous year, has strained the relationship. Dr. Kwon said that this demand from the US was unprecedented, and has caused many to reconsider American commitments. General Lute also pointed to troop withdrawals from Germany as a potential forewarning for future Trump policy in East Asia. Recently, Japanese officials have been more willing to articulate its positions of certain policy issues, even if this runs counter to the US position. Still, Ms. Tatsumi notes that Japanese officials continue to use other elements of international power besides military to leverage its interests.

Other effects of American politics on these security relationships were addressed. General Lute stated that alliances and leadership start at home, and denigrating American institutions means that the US cannot portray itself as a good model elsewhere. Ms. Tatsumi went as far as to claim that reelecting Trump would deal a body blow to Japanese confidence in the US. Dr. Kwon agreed; the US-South Korea alliance has had its ups and downs, but South Korean officials had not questioned the US commitment to East Asia before the Trump Administration. These days, some Koreans speak of moving from the asymmetric alliance with the US to a more flexible security partnership.

Chinese aggression in the East China Sea and particularly the contestation over the Senkaku Islands means that the People’s Republic of China remains a present threat to both Japan and South Korea. American relations with both countries along with its relationship with Taiwan keep the US engaged with the region, but the Trump administration’s unpredictability only adds to the anxiety over these countries’ alliances with the US.

All agreed that a Biden victory in the 2020 election would shift how alliances are treated by the US. General Lute cited Biden’s decades of experience of the value of alliances and the importance of these networks in solving problems that defy national boundaries, like COVID, climate change, and migration. Ms. Tatsumi argued that Biden would return predictability and confidence in US behavior and would end the portrayal of alliances as transactional entities. South Korean officials likewise see Biden as someone who values alliances more, and he can, according to Dr. Kwon, “bring US leadership back on track.”

When examining US alliances, many are in a state of flux, but this is the norm for international relations. American alliances have weathered numerous ups and downs, and the present challenges that they face are by no means a death knell. Trump’s administration has degraded alliances with NATO, Japan, and South Korea. Still, these alliances are likely to last. It is important to keep in mind that they will only survive if American leadership values these alliances and devotes resources to maintaining credible commitments to its partners.

Prepared by Courtney Kayser, PhD. Candidate at the Schar School

Session 3

Security Cooperation and Partnerships

Featuring

Catherine Owen, Exeter University

Ambassador Mark Lippert, Former Defense Dept. and White House Official, Former Ambassador to South Korea

Dalia Dassa Kaye, Senior Political Scientist at the RAND Corporation and former Director of RAND’S Center for Middle East Public Policy

Moderator: Michael Hunzeker

The third and final panel considered security cooperation arrangements that are not formal alliances. Moderated by Schar School Professor and Associate CSPS Director Michael Hunzeker, the panel comprised Mark Lippert, former U.S. Ambassador to South Korea and veteran of the both the Defense Department and the White House; Dr. Dalia Kaye, Senior Political Scientist at the RAND Corporation, and Dr. Catherine Owens, Post-Doctorate Fellow at Exeter University.

Mark Lippert reflected on how the United States views its various national security partners. He noted that while these relationships are quite variable, from strong relationships between the U.S. and partners like Singapore and New Zealand, to looser, more amorphous relationships with other states. Across the range, these security relationships are mutually beneficial as long as U.S. partners act in a manner consistent with American values. Mr. Lippert also discussed the nature of the U.S. security partnership with Taiwan, noting that both the Obama and Trump administrations have made efforts to build a relationship with Taiwan short of formal recognition. Another such challenge is the widespread perception of a lack of interest, and in some cases outright hostility, among the American people regarding security partnerships. Mr. Lippert noted that there is public opinion data suggesting broad support among the American public for engagement overseas, so he is optimistic that the next administration will be able to successfully pursue these types of security partnerships. He also argued that in healthy alliances, additional institutions, such as economic commissions or other platforms for shared civilian cooperation, can build resilience and societal buy-in for security commitments.

Dalia Kaye noted that while there are no formal alliances between the U.S. and any Middle Eastern country (other than Turkey through NATO), there are several risks entailed in creating security partnerships in the region. Reputational risks, risks of entrapment in conflicts unrelated to U.S. interests, and the potential for leadership changes in partners are all factors that the U.S. must price into any partnership it wishes to pursue in the Middle East. Dr. Kaye also highlighted the challenges that great power competition has created for U.S. security partnerships. Many Middle Eastern countries are expanding their ties with U.S. adversaries like China and Russia, and the current U.S. strategic focus on great power rivalry is reflective of this reality. In addition, Dr. Kaye argued that the American withdrawal from the Iran nuclear agreement, the JCPOA, has led to a credibility problem for the U.S. Even if a potential Biden administration were to rejoin the nuclear deal, it is unclear if the Iranians will be interested in having the U.S. as part of the agreement again.

Catherine Owen discussed Russian and Chinese activity in Central Asia. She argued that both China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union represent efforts by these great powers to minimize space for Western influence in the region. However, Dr. Owen noted that the BRI primarily represents a response to China’s domestic economic concerns, and many aspects of the program existed before the BRI was formally enacted by Xi Jinping. On the issue of security partnerships between Russia and some of its post-Soviet allies, Dr. Owen discussed the fact that Russia is currently supporting the Lukashenko regime in Belarus, so the prospects for any form of American security cooperation with countries where Russia actively supports autocratic regimes is minimal. Dr. Owen’s remarks again highlight the point that great power competition may serve to define the nature of security partnerships for the foreseeable future, with the Central Asian states playing Russia and China off each other, to avoid binding commitments and to optimize their sovereign independence.

Prepared by Tim Bynion, PhD candidate, Schar School